By Dr. Charles Gallagher, SJ

The history of the Diocese of St. Augustine, which now comprises lands where Catholicism first touched the shores of North America above Mexico, cannot be condensed or encapsulated without doing a large disservice to many events of profound historical importance.

Decades prior to the establishment of a stable Catholic mission at St. Augustine, rituals of the Catholic faith were practiced by associates of the Spanish explorers Juan Ponce de Leon (1513) and Tristán de Luna (1559). The so-called “pre-history” of the Diocese of St. Augustine represents a period of great consequence in charting the history of Christianity on the Atlantic Seaboard. Accordingly, the reader is encouraged to consult the Recommended Readings list at the conclusion of this essay for more in-depth and contextualized treatments of the advancement of Catholicism on the flowered peninsula.

Three Centuries Under the Sun: Diocesan Pre-History (1565-1870)

In the early 16th century, Florida was at the leading edge of Christian expansion in the New World. One historian has described the peninsula as “Europe’s first frontier in North America,” a fact of history that largely has gone unnoticed in popular written histories of the United States. Over half a century before the English landed at James Town (1607) and Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock (1620), Spanish Catholics had explored, settled and fortified the small city of St. Augustine on Florida’s northeast coast. In 1565, the expedition of the Spanish “Captain of the Indies Fleet,” Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Aviles first sighted Florida’s gleaming whites coasts. Menéndez’ sailors had been at sea for nearly three months when they spotted land on August 28th, the feast day of the famed theologian, convert and North African bishop, St. Augustine of Hippo. Immediately, Menéndez ordered the singing of the traditional Te Deum hymn – “Oh God we praise thee, and acknowledge you as supreme Lord.” The flotilla took some days to survey the coastline from their ships. When Menéndez and his band of 1200 Spanish conquistadors finally made landfall on Sept. 8, 1565 they decided to name the spot of their landing St. Augustine.

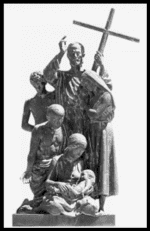

Menéndez claimed the land for God and for Spain, even though the fleet’s chaplain, Father Francisco López de Mendoza Grajales indicated that “a large number of Indians,” watched intently as the expedition arrived on the shoreline they had inhabited for centuries. What the Native Americans witnessed was the first Roman Catholic Mass to be celebrated in a permanent settlement of European origin in the United States. One historian has described the scene with flourish: “Amid the booming of artillery and the blast of trumpets the standard of Castile and Leon was unfurled. The chaplain, Father Francisco Lopez de Mendoza Grajales, carrying a cross and followed by Spanish troops, preceded to meet the general who advanced to the cross. He kissed the cross on bended knee, as did those of his staff. The solemn Mass of Our Lady’s Nativity was then offered.”

After the Mass, Father Grajales began work on the mission church he named Nombre de Dios – name of God. The site and the mission would be home to the first permanent Christian house of worship on the Eastern Seaboard. It was, for all intents and purposes, the “first parish church” in the United States – administered through the Diocese of Santiago in Cuba. Except for 20 of the next 200 years, St. Augustine would remain under Spanish rule and earn the nickname “la siempre fiel ciudad” – “the ever-faithful city.”

Through the Mission Nombre de Dios, the Roman Catholic faith remained an integral part of St. Augustine as its fortunes waxed and waned through the Spanish colonial era. Months prior to Menéndez landing in 1565, to the north of St. Augustine French Protestants, known as Huguenots, were spotted building a small settlement and fort on the mouth of the St. Johns River near present day Jacksonville. In 16th and 17th century Europe, the struggles between nations often involved a religious component. These were the so-called “Iron Times,” of the Wars of Religion. Such tussles were transferred to the New World, where boundary disagreements and strategic trade disputes were often cloaked in the mantle of emotion-laden religious pride.

In September and October of 1565, Pedro Menéndez attacked a fledgling settlement of French Protestants at Fort Caroline, on the mouth of the present day St. John’s River. Menéndez spared the women and children of Fort Caroline, but Christian charity did not prevail for more than 300 French soldiers marooned south of Fort Caroline. Blown off-course by storms while on their way to St. Augustine for the purpose of attacking the Spanish there, French commander Jean Ribault and his soldiers were found stranded and were ruthlessly executed by Menéndez on a beach 14 miles south of St. Augustine now named Matanzas (Place of Slaughters). The brutality of this action prompted the French to quit all claims to Florida. Menéndez, a man of restless energy, then gave full reign to Catholic missionaries to begin evangelization of the native population of St. Augustine and environs. In the next decades, a “golden age” of Catholic missionary activity emerged in Florida.

In an era when Roman Catholic Church leadership was held firmly by clerics, Father Grajales broke with tradition and began to appoint Spanish soldiers to the task of instructing Native Americans in the rudiments of the Roman Catholic faith. This move had a double effect. Over time it impelled Spanish soldiers to marry Native American women, creating what historian Kathleen Deagan has called a Catholic “Mestizaje” class in Spanish St. Augustine. In addition, by the early 17th century a so-called “domestic church” arose, adequately feminized to the point that one missionary reported to his Spanish superiors “Indian women were the most fervent and enthusiastic converts and were used as catechists to help convert other Indians.”

Over time, religious orders of men would be sent to Florida to spread the Gospel in the missions. The Society of Jesus, better known as Jesuits, were sent in 1566 by Jesuit General St. Francis Borgia. More were sent in 1568, but due to setbacks, including the killing of some Jesuits by hostile Native Americans, the Jesuits pulled out of Florida in 1572. The Franciscans arrived in 1577 and met with better success until 1597, when a general revolt led to the indiscriminate murder of many missionaries. By the early 17th century the Franciscans missionary efforts were bearing great fruit. In 1655, there were 70 Franciscan Friars working a chain of mission outposts from St. Augustine west to the Tallahassee Hills. This sophisticated “mission chain” of the Franciscans tallied a remarkable 26,000 Catholic Native Americans. The days of Catholic missionary prosperity began to ebb by the start of the 18th century. This time the threat was not from the French, but from a burgeoning new empire.

By the turn of the 18th century, British colonists had reached the Carolinas and looked southward to expand commercial and land interests. The presence of Spanish Catholics in North Florida was an affront to Colonel James Moore and his band of Carolina soldiers. They attacked Florida in 1702 and destroyed the city of St. Augustine, in the words of one historian, amid “burning, plunder, carnage, and enslavement.” While Moore was unable to capture the ever-durable fortress Castillo de San Marco at St. Augustine, within two years he embarked on a campaign to eradicate all the Franciscan missions of Florida. The operation was successful to the point that by 1763 there were only four missions left on the peninsula, serving 136 Catholic Native Americans. In the 19th century, Catholic historian John Glimary Shea called Moore’s campaign a form of religious cleansing and his extermination of the Apalachee missions “a mark of English provincial hatred against the church of God.” Modern observers see the maneuver as a warning tremor prior to Queen Anne’s War and the larger intercolonial struggles for control of Florida’s gulf coast.

British forays from the Carolina’s continued throughout the early 18th century. In 1763, Philip II’s wish of two centuries earlier that Pedro Menéndez might “clean the seas” of French and British interlopers fell flat as the Spanish crown lost Havana, Cuba during the Seven Year’s War (1756-1763; known as Queen Anne’s War in the American Colonies). Spain was forced to make a hasty exit from Florida. Within ten months, all soldiers, citizens, missionaries of Nombre de Dios and nearly 200 Catholic Native Americans removed themselves from St. Augustine and headed to Cuba or other Spanish territories. Catholicism was all but snuffed out on the peninsula.

Then, in 1768, Catholics abruptly returned to St. Augustine and remarkably, were given a modicum of consideration by the British authorities. The case was brought about by a rebellion of indentured servants tied to the Scottish physician and entrepreneur Dr. Andrew Turnbull of New Smyrna. Turnbull hoped to cultivate indigo, which was bringing an enormous price in Europe, in the low sea-plains of New Smyrna. He recruited a group of about 1200 workers from the island of Minorca as well as some Italians, Greeks and Corsicans. Among them was a Catholic priest, Father Pedro Camps. In New Smyrna, Father Camps built a structure, little more than a shack, and consecrated it St. Peter’s Church – the first functioning Catholic worship space in Florida during

the British occupation. Over time, Turnbull reduced the Minorcan laborers to no more than chattel slaves. When Turnbull reneged on his promise of freedom at the end of the workers’ indenture, Father Camps called attention to the Scottish physician’s injustice. Camps and the Minorcans gained the sympathy of the English attorney general in St. Augustine and were given free passage to the “Ancient City” in July of 1777. During this migration of about 70 miles, Father Camps attended to the infirm, women and children of the colony. And as a dutiful priest, he took pains to perform baptisms, marriages and funeral rites for the Minorcan community. His sacramental records provide valuable historical evidence of the Minorcan communities in both New Smyrna and St. Augustine. In compendium form, they are commonly referred to as the “Golden Book of the Minorcans.”

The Minorcans maintained very good relations with the British, but changes in the political landscape meant that old overseers would return and reconstitute Florida’s religious infrastructure. In 1784, Florida was restored to Spain as a consequence of the peace treaty that ended the American Revolution. “The colony is ceded and guaranteed to the Crown of Spain,” a despondent Englishman wrote at the time, “to be delivered up and empowered by his His Most Catholick Majesty.”

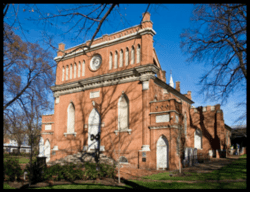

The Minorcan community opted to stay in Florida rather than withdraw with the British. Soon they were joined in St. Augustine by some of the Spanish who had departed 20 years earlier. Father Thomas Hassett, an Irishman trained in Spain, was assigned to St. Augustine. Within a few years, Father Hassett started a program of catechetical instruction for African-Americans who were brought to Florida in chains for the purpose of plantation slavery. In 1797, the façade of a Spanish-style Cathedral was formally dedicated. The Cathedral parish served as worship space for Catholics of all races.

Within its sanctuary, a certain number of marriages took place between African-Americans and Spanish Catholics. More common were baptisms of Catholic children born of Catholics and African-Americans, with various religious rights being passed to slave children. One example is found in Zephaniah Kingsley, a fabulously wealthy plantation owner in what is now Duval County, who took Anna Magigene Jai, the daughter of an African chieftain, as his acknowledged wife. While the couple was married outside the church, Anna remained a devout Catholic and throughout the early 1800’s made sure that priests from the Cathedral in St. Augustine traveled to the Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island to baptize each of their four children. The rather flexible racial and religious configurations would fall to a more rigorous approach as Florida experienced yet another change of hands.

The “Second Spanish Period” ended in 1821, when Spain reached an accord with the United States and relinquished Florida for the sum of $5 million. The hearty Father Hassett and his assistant at the Cathedral, Father Michael O’Reilly, watched as the Spanish left Florida leaving only about 600 Catholics in the territory. In 1819, Florida was placed under the jurisdiction of what was then the Diocese of Louisiana. The bishop, Louis William Dubourg, never visited Florida since the territory gained a reputation, in the words of one historian, as “a garrison town in a remote and undesirable frontier.” By 1850 the unexpected changes of state, religion, warfare and economic disintegration had taken their toll. Of the 1200 Catholic churches in the United States at the time, Florida only had five. And compared to the 170 Protestant churches in Florida, Catholics represented only a small remnant from the golden missionary age. The erratic changes in civil governance were reflected, also, in Catholic attempts to religiously administer the extensive peninsula.

Since the landing of Menéndez in 1565, the lands that would later become the Diocese of St. Augustine were placed under a dizzying series of religious jurisdiction. Successively, these included the Diocese of Santiago de Cuba (1565-1787), Havana (1787-1793), the Diocese of Louisiana and the Florida’s (1793-1825), the Vicariate of Alabama and the Florida’s (1825-1829), the Diocese of Mobile (1829-1850), the Diocese of Savannah (1850-1857). In 1845, Florida entered the United States at the 27th state, signaling its political development and the stability of boundaries. In 1857, Roman authorities saw fit to designate Florida a Vicariate Apostolic – a missionary district where a chosen cleric is given ecclesiastical jurisdiction. In the case of Florida, Pope Pius IX nominated a French-born priest from Baltimore to be the person in charge.

In December of 1857, Augustin Verot was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Florida. Verot was a man of deep faith and learning. A priest of the Society of St. Sulpice, from 1830 to 1853, he taught philosophy, theology and science at St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore. From 1853 to 1857, his suitability for hardship duty was noticed as he engaged successfully in missionary work in Ellicot Mills, Maryland. In early 1858, he was consecrated titular Bishop of Danabe and sent south. In late 1861, Verot pulled double-duty being appointed the third Bishop of the Diocese of Savannah, Georgia upon the untimely death of its bishop. For more than ten years he shepherded the Diocese of Savannah and attended to the Vicariate of Florida, making many improvements to churches in Jacksonville, Key West, Tampa and Tallahassee.

“Florida is a big state in area but her people are comparatively few and the settlements are far apart,” Floridian writer Susan Bradford Eppes wrote in her diary in 1860, precisely summarizing the landscape that Bishop Verot inherited as Vicar Apostolic. Remarkably, Verot visited even the remotest parts of Florida. He traveled on horseback to visit scattered Catholic families and settlements, offering Mass and often sleeping outdoors under the stars. In March of 1870, Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of St. Augustine and named Augustin Verot its first bishop. Its boundaries included all of Florida except for the portion west of the Apalachicola River. In total, the diocese spanned a vast 46, 959 square miles. All told it was 305 years from the celebration of Father Grajales’ first Mass in St. Augustine to the formal establishment of the diocese.

Charles R. Gallagher, Ph.D., is a Jesuit with the New England Province. He is a former archivist for the Diocese of St. Augustine (1997-1999) and author of, Vatican Secret Diplomacy: Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII, which won the John Gilmary Shea Prize, an annual award given by the American Catholic Historical Society. He is also author of Cross & Crozier: A History of the Diocese of St. Augustine. Father Gallagher, ordained June 12, 2010, has been assigned to the Department of History at Boston College.

Rebel Bishop: Augustin Verot, Florida’s Civil War Prelate by Michael V. Gannon, Ph.D.,

University of Florida Press – Gainesville; Reprint edition, 1997.

Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic Church in Florida, 1513-1870 by Michael V. Gannon, Ph.D., University of Florida Press – Gainesville; 2nd edition, 1983.

Catholicism in South Florida: 1868 -1968 by Father Michael J. McNally, University of Florida Press – Gainesville, 1984.

Catholic Parish Life on Florida’s West Coast by Father Michael J. McNally, St. Petersburg, FL: Catholic Media Ministries, 1996.

Cross & Crozier: A History of the Diocese of St. Augustine by Charles R. Gallagher, Ph.D., Éditions du Signe – Strasbourg, France, 2000. Cost: $15. To order a copy of Cross & Crozier, email: kbagg@dosafl.com.